Por LIGIA LEE G.

Licenciada en Relaciones Internacionales y Asuntos Exteriores, Universidad Rafael Landívar

Magíster en Ciencia Política con Mención en Relaciones Internacionales, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile

*Publicación autorizada por The Affiliate Network y Navisio Global LLC.

In the last three years, Presidential politics brought a series of changes to Latin America that seem to signal a shift away from the ideology of the Left. Though the shift is not (yet) a region-wide trend – Maduro, Ortega, Morales, and others still hold leftist power – it is significant enough in the large southern economies to raise eyebrows in Caracas, La Paz, and other left-leaning capitals. Recent Presidential elections in Brazil, Chile, and Argentina are noteworthy, not just for their potentially large economic impacts on Latin America, but because the voters there cast off their left-leaning leadership despite their own dark memories of right-wing governments.

Though the shift may be a response to socialist governance that struggles with corruption and effectiveness, it follows a global rightward trend energized by a populist desire for something different. The most recent election results were disappointing for incumbents in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Guatemala, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, and Peru. Most of those went to right-of-center candidates and some represented a complete ideological about face. Whether driven by ideology or simply voter frustration with those in charge, a change is in the air in Latin America and it does not look good for the Left.

Kirchner Leads the Way

The electoral downfall of Argentina’s President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner is an example of voter frustration with an incumbent. The wife of former President Nestor Kirchner, Cristina inherited his political identity as Argentina’s Peronist candidate, a reference to the popular President Juan Peron and the political movement he inspired. Considered the dominant political ideology in the country’s modern history, Peronist candidates have won nine of Argentina’s last 12 elections. Cristina’s “accession” to the Presidency as supported by her husband, entrenched the “Kirchner Clan” in Argentine politics in a manner reminiscent of some of the worst aspects of Peronism (the heavy-handed Peron was also succeeded by his wife). Cristina’s penchant for glamour and graft further entrenched the Kirchners in the economy, society, and courtrooms of the country.

Once she was out of power, the Argentine legal system began to investigate her corruption and that of her husband; actions which some view as the government simply catching up with what the people already knew. In October 2018, a judge began an investigation of Mrs. Kirchner and her children, Florencia and Máximo, for money laundering. Though this news drew significant media attention, it is not the only case being brought against Mrs. Kirchner. The state is also investigating her for irregularities in awarding public contracts to Grupo Austral in the province of Santa Cruz, the cradle of “Kirchnerism.”[1]She is also being investigated for defrauding the government through the dollar futures market, for trying to cover up the Iranian bombing of a Jewish center in Buenos Aires, and for several other charges related to the abuse of power.

The ideological, political, and social division between the “Macristas” and “Kirchnerists”.

Photo credit: https://www.elintransigente.com/politica/2017/6/14/cristina-kirchner-difundio-duro-documento-contra-macri-441000.html

Nevertheless, Mrs. Kirchner’s ability to survive elections in order to stay in power cannot be denied. Now a Senator, Kirchner claims with some success she is a victim of persecution by her successor, Mauricio Macri. Despite the polarization between “Macristas” and “Kirchnerists”, she remains popular in large part due to welfare programs she implemented while President. Under her administration, however, subsidies designed to support social groups did nothing to contribute to the country’s economy and led to a large internal debt Macri has been unable to completely reverse. He now suffers from a relatively low approval rating because of external debt generated in part, by International Monetary Fund loans intended to manage the deficit caused by the Kirchners. Sensing opportunity, Mrs. Kirchner is widely expected to run for President again in 2019.

Return to the Right-Wing

One can clearly see a return to the Right in Chile with the end of Michelle Bachelet’s Socialist Party administration and the re-entry of rightist ideologue Sebastián Piñera in 2017. The case of Mrs. Bachelet is similar to that of Mrs. Fernández in that both were the first female leaders of their countries and both came from leftist political parties. The similarities end there, however. Mrs. Bachelet is not part of a family dynasty or the embodiment of a cultural-political movement like Peronism. In the comparatively healthy political environment in Chile, she has traded the Presidency with her right-wing rival for the last 16 years.

At the beginning of her first administration – 2006-2010 – Bachelet had a very high approval rating. Chilean voters had elected her with 53.9% of the vote; giving her a healthy seven-point margin and control of 12 of the country’s 13 regions. Her 2014 election was even more convincing when she won an astonishing 62% of the votes; setting up her second administration with a solid mandate for a more progressive program. Among her most notable achievements were the abortion law; the enactment of a union civil law; and the enfranchisement of Chileans abroad. Chilean Presidential politics is a balancing act between Left and Right however and the center-left political group she represented was no longer welcome in Chile. Whispers of corruption began to erode her still great popularity.

Mrs. Bachelet and Mr. Piñera, representing the political change in Chile. Photo credit: https://radio.uchile.cl/2018/03/10/bilaterales-marcan-ultimo-dia-de-michelle-bachelet-y-pinera-antes-del-cambio-de-mando/

In 2015, a company partly-owned by Bachelet’s daughter-in-law was investigated for use of privileged information and influence peddlingin connection with a land sale. The company, “Caval Limited”, became known as Bachelet’s “secret business” and caused her approval rating to plummet to 35% in a single month in March 2015. By the time of the 2017 election, the desire for change was no surprise. Piñera won a clear victory, with 54.5% of the votes, a nine-point margin over the left-leaning Alejandro Guillier (a social democrat).

Ultra Shift

Brazil provides another example of the shift from Left to Right. In an ideological continuation of rule by the left-leaning Partido de los Trabajadores (PT), Dilma Vana Rousseff won the presidential election in 2010. Though she commanded only a narrow 51.64% of the vote, the win was seen as significant for PT which ruled in Brazil for the preceding 13 years. Rousseff, the first female President of Brazil, hoped to emulate her former boss, President Lula da Silva whom she served as Chief of Staff and Minister of Energy. At the time Lula left office, he was the most popular politician in Brazilian history, enjoying approval ratings of 80%. Like Kirchner however, Rousseff’s corruption prevented her from capitalizing on the widespread popularity of her predecessor. In 2016 she was impeached by the Brazilian Senate for violating fiscal rules and removed from office.

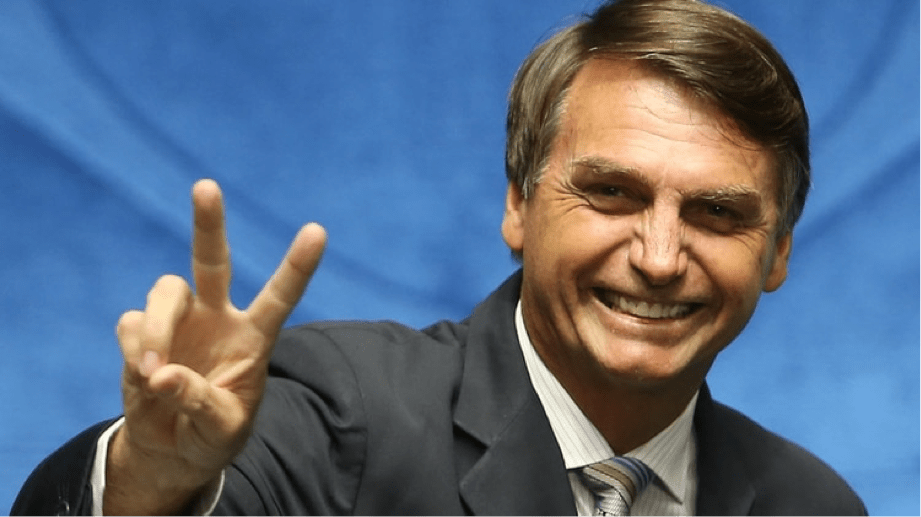

Dilma’s impeachment and Lula da Silva’s incarceration on influence peddling charges left PT without a strong candidate in the 2018 election. Reflecting the electorate’s frustration with 13 years of PT corruption, Mr. Jair Bolsonaro, a former Army officer and an “ultra-right” candidate, won the presidential election by a whopping 11 points. Bolsonaro seems like a hard sell in free-wheeling Brazil. A constant stream of offensive comments has been the hallmark of his 30-year political career. Among other things, he has publicly said: he wouldn’t hire men and women with the same salary; he would be unable to love a homosexual son; and that Afro-descendants don’t do anything and shouldn’t procreate. Yet as shocking as he can be, he is the candidate that best embodies the Brazilian people’s disillusion with the Left.

Mr. Jair Bolsonaro. Now President of Brazil Photo credit: https://www.infobae.com/america/america-latina/2018/11/28/estados-unidos-califico-de-oportunidad-historica-la-eleccion-de-jair-bolsonaro-como-presidente-de-brasil/

Indigenous Axis

Evo Morales Ayma has been the President of Bolivia for a record 13 years. He became the country’s first indigenous leader when he was elected in 2005 with 53.7% of the vote. His reelection in 2009 with 64% of the vote signaled that Bolivia had moved firmly away from the non-indigenous, largely right-wing politics of its past. When he won again in 2014 with 61.3% of the vote he seemed unstoppable. His affinity for Venezuela’s socialist icon, Hugo Chavez, was a cause for concern throughout the hemisphere and particularly in Washington which believed they presented an alternative form of left-wing governance that threatened the established order on the continent.

Morales’s political machine appears to be losing momentum, however. Perhaps sensing danger in the state of post-Chavez Venezuela, the Bolivian electorate is expressing a desire for change. The shift in opinion was evident in the results of a referendum on presidential term limits that would abolish term limits and allow Morales to run again in 2019. Not only was this his first electoral defeat in a decade, but it was a clear rejection of his continued leadership of the country.

Mr. Evo Morales with Mr. Maduro (R) and Mr. Correa (L) in 2015. Photo credit: http://www.la-razon.com/nacional/Frases-presidentes-Correa-Maduro-Morales_0_2361363938.html

End of the Left?

Latin America has a long and difficult history of abuse at the hands of right-wing governments, a fact that makes the rightward trend of electoral politics there a somewhat surprising development. Corruption has played a big part as leaders from both Left and Right have been found guilty of using their positions to benefit themselves and their cronies but it is the Left, which held the majority of Presidencies in the region for the last 15 years, that is receiving the brunt of voter frustration.

The failure of the socialist dream in Venezuela is also having far-reaching consequences with well over a million Venezuelans fleeing privation and despair in what used to be the region’s wealthiest nation. The significance of the exodus cannot be lost on voters struggling to reconcile their fears of a right-wing resurgence with their frustration over systemic left-wing corruption. Though it may be too soon to declare the end of the Left, there is a clear desire for change that will leave its mark on elections in 2019.

[1] Kirchnerism is poorly defined and probably cannot be considered a political movement in its own right. It can probably best be described as an extension of the heavy-handed left-wing political philosophy of Juan Peron.

*Imagen de cabecera propiedad de The Affiliate Network.