Por TOMÁS CROQUEVIELLE H.

Licenciado en Historia y Periodista

Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile

Eduardo Frei Montalva was the first progressive president in Chile. Through social Catholic activism, Frei became a node in Chilean history, promoting third-way politics between socialism and laissez-faire capitalism long before Bill Clinton and Tony Blair. And Frei’s assassination, ordered by the dictatorship, could not vanquish the political dynasty that retains much clout in Chilean politics.

Last week, a court sentenced six people to up to 10 years in prison for the killing of Eduardo Frei Montalva in 1982. This was the first probed case of magnicide ever in the country. But where did Frei Montalva come from and why exactly was he important? Why was he killed?

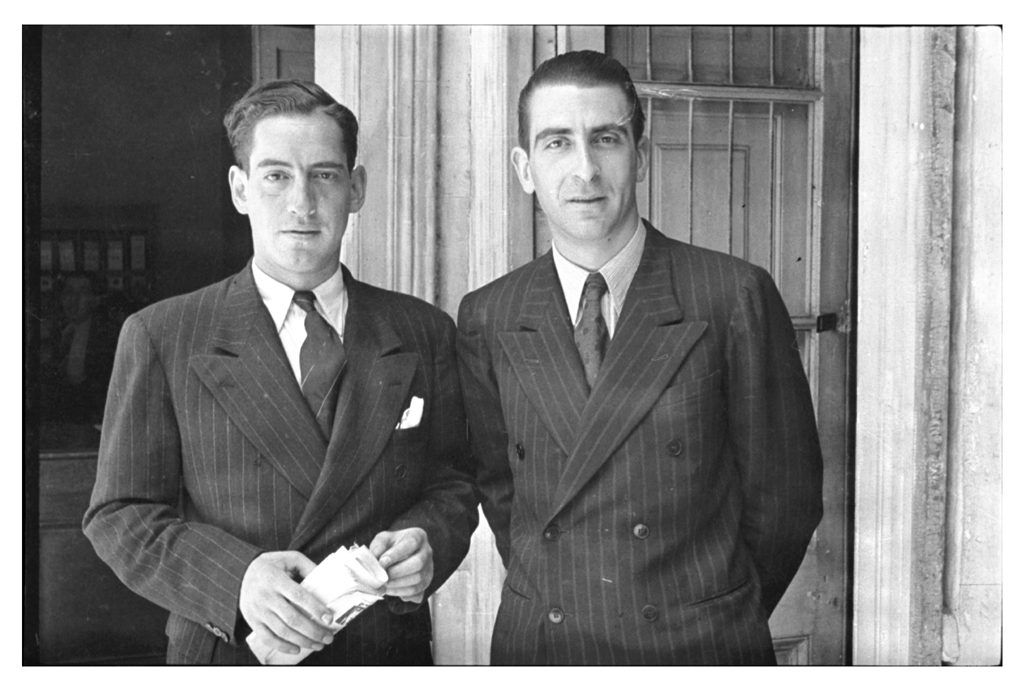

Born on January 16, 1911, in Santiago to Austrian immigrant Eduardo Frei Schlinz and Chilean Victoria Montalva Martínez, Eduardo eventually founded a political clan that occupied positions in government over decades.

Eduardo’s first son, Eduardo Frei Ruiz-Tagle, was president from 1994-2000, his daughter, Carmen Frei Ruiz-Tagle was senator from 1990-2006, and his nephew Arturo Frei Bolivar was deputy (1969-1973), senator (1990-1998) and ran as independent presidential candidate in 1999.

His sister, Irene Frei, was mayor of Santiago in 1963. She perished in a car accident months before her brother became president.

Early social vocation

While studying Law at the elite Catholic University, Frei joined the “young conservative Catholics,” a group linked to social Christian thought.

His 1933 thesis on the possible abolition of the salary regime earned him the university’s highest honor. Ever since, social concerns remained the cornerstone of his political career.

Through engaging in social Christian enterprises like the Catholic students’ magazine, the Catholic students’ national association and the youth arm of the conservative party, Frei developed a social conscience that shaped Chilean politics deeply.

A meteoric career

After being a professor, lawyer, and writer for conservative newspaper Diario Ilustrado of Santiago, and director of El Tarapacá newspaper in Iquique, Frei entered politics when he helped create the National Falange movement which turned into a political party. His career took off after he assumed the Falange presidency. He became public works minister in 1945 and was elected senator for Atacama and Coquimbo in 1949.

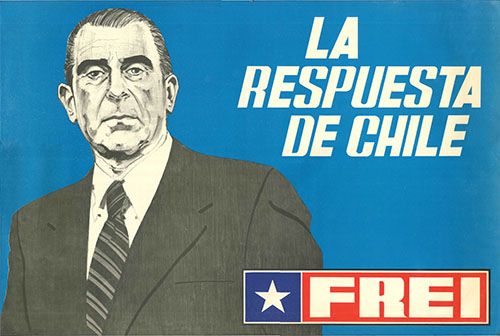

In 1958 Frei ran for president with the Falange successor, the Christian Democratic Party (PDC). He got 20% of the vote while right-wing Jorge Alessandri Rodríguez won with 31.5%. Socialist Salvador Allende came in second with 29%, a margin of only 34,000 votes.

In 1964, Frei ran again. This time he won a landslide 56%, in part thanks to the right, which supported him to keep Allende out. Frei’s campaign and party also received help and funding from the CIA, because Washington worried of the example Allende could set.

Revolution in Freedom

During his presidency (1964-1970), Frei focused on his ambitious “Revolution in Freedom” program. Through this program he sought a structural transformation on every level, but within the Constitution, respecting laws and liberties. This “third way” was meant as alternative to Soviet revolution and capitalism alike.

Key achievements of Frei’s progressivism were an education reform that opened education to poorer citizens.Under his government the housing and urbanism ministry was created, which oversaw the construction of nearly 130,000 low-cost houses.

Frei’s signature and most far-reaching policies, however, were the 1965 Agrarian Reform and the 1966 “Chileanization” of the copper industry.

Chileanization allowed the state greater ownership of mines – until then wholly-owned by US companies – by gradually buying 51% of key assets such as El Teniente and Andina. Control went to the newly created state-run Copper Corporation (Codelco), which is still the main source of revenue for the treasury.

His agrarian reform broke up large estates, eliminating an agrarian economy that had dominated the countryside for over three centuries. Peasants were allowed to unionize, and agricultural production became more dynamic. Hence, the agro-industry grew for decades, and both Allende and Pinochet expanded that reform. Chilean agribusiness eventually became the most important food supplier to world markets.

Even the US supported the reform as part of an Alliance for Progress. Yet, due to its profound impact on the social fabric, the reform also nurtured a desire in the upper classes for a strongman to ‘restore order.’

Another aspect of Frei’s deep changes, apart from rising unionization and income redistribution, is found in “Promoción Popular” (loosely Popular Promotion). This policy modified the forms of collective organization. It facilitated cooperatives, neighborhood associations, youth organizations and mother centers, which under the objective of social justice were to improve the lives of Chileans, the majority of which was poor.

Polarization and crisis

Despite the achievements, the reforms also affected individuals negatively. So in those hyper-polarized times the left attacked them saying they were too soft, and the right accused Frei of leading the country into socialism. High inflation trounced the poorest and represented an additional headache for the government.

Many voters, especially an energized the left-wing, considered therefore a centrist platform unreasonable in the 1970 election, resulting in the victory of Salvador Allende, who ran for the Popular Unity (UP) coalition. Frei became a hardline critic of Allende’s policies.

Opposition to dictatorship

In the parliamentary elections of March 1973, the former president was elected senator for Santiago and rose to the presidency of the Senate.

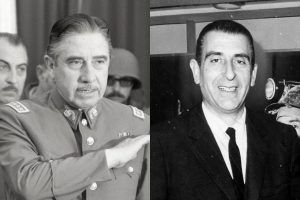

Betting on short military rule that squashes Allendeism and promptly paves the road to new elections, Frei supported the coup in September 1973. But as the junta strengthened its bloody grip, Frei began to challenge the generals. Too late – the dictatorship had complete control and installed a neoliberal system that ran counter to his ideals of inclusiveness and democracy.

A threat

During the early 1980s, Frei became the face of the resistance to Pinochet. He was keynote speaker at the Caupolicanazo, a mass opposition event attended by Christian Democrats and socialists alike. The regime authorized only this rally in the Caupolicán Theater in the wake of the 1980 campaign – normally dominated by the dictatorship – for the “referendum” (held without electoral records) on the new constitution.

Frei’s appeal frightened the rulers. They saw the possibility of a Christian Democrat-left alliance, which they sought to prevent by assassinating Frei. The dictatorship figured it could get away with killing major opponents. In 1974, it had General Carlos Prat killed in Buenos Aires and in 1976 Orlando Letelier in Washington, DC, without major repercussions. In late 1981 Frei underwent a simple surgery but died on January 22, 1982 after several “unexpected complications” which a judge recently categorized as murder.

But even in death, Frei challenged the dictatorship. During his tense funeral, four chairs remained empty, representing the absence of major PDC figures Andrés Zaldívar, Claudio Huepe, Renán Fuentealba, and Jaime Castillo Velasco who were barred from entering the country from exile. Cynically, however, Pinochet attended.

As a challenge to the regime, his funeral also laid the foundation for reconciliation with the historic rival, the Socialist Party. Shortly after, the socialists called Frei “an important factor in the struggle for democracy” in this “time and repression.” Later the Democratic Alliance and Coalition of Parties for Democracy, built on this premise and united most of the opposition against the regime during the 1980s.

Due to the political capital and social prestige Frei accumulated with his resistance, he would have been a serious contender for the first post-dictatorship presidency had he not been killed. Instead, Eduardo Frei Montalva became, so far, the the highest profile victim of Pinochet’s bloody dictatorship.

The death of Pablo Neruda and others is also being investigated on suspicions of poisoning by the dictatorship apparatus. So even after decades, many secrets remain regarding the deaths the military regime has caused.

*Imagen de cabecera propiedad de Centro Cultural La Moneda.