Por TOMÁS CROQUEVIELLE

Periodista y Licenciado en Historia

Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile

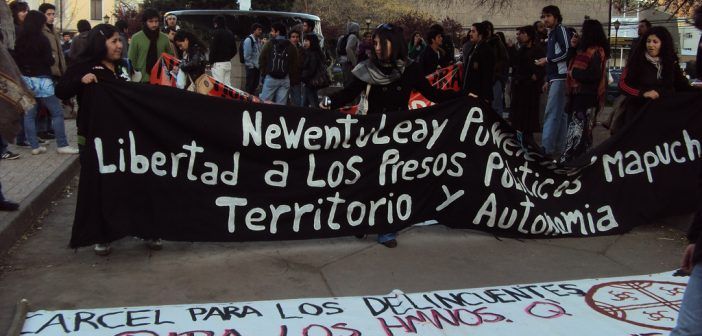

Mobilization and social response have reached new heights of intensity since Mapuche comunero Camilo Catrillanca was killed. At the same time, the Piñera administration has been criticized for its hardline policy in the region and accused of inspiring radicalization in the conflict.

After the terrorist attack of Tarata in 1992, the Peruvians of Lima realized the gravity of the conflict that was being fought in the countryside between the guerrillas and the army.

This November 2018, the people of Santiago are discovering the intensity of the conflict that is occurring in the Araucanía region – one that has, for approximately a decade, pitted the Mapuche communities, on the one hand, and the wood industry and the State, on the other, against each other. The violence from the rural areas of the south of Chile is moving to the capital.

Information about Catrillanca’s death has been confusing at best

Since November 15, several serious incidents have taken place across Santiago. All of them have a common denominator: spontaneous protest against the death of Camilo Catrillanca, 24, a “comunero” Mapuche shot in the head in a confusing incident involving the special task force of Carabineros, Grupo de Operaciones Policiales Especiales (GOPE), in Temucuicui, in the north of Araucanía.

While killings involving government forces and Mapuches are always incendiary, this one is especially so because the information released to the public about it has been confusing, at best, and profoundly disturbing, at worst.

It is therefore no surprise that simmering anger is now boiling over.

A series of violent events in Santiago

The first such event in Santiago occurred last week following a peaceful demonstration in the center of the city that coincided with a call to protest the contamination that has affected the Quintero comuna since August. The demonstration, however, devolved into different acts of violence that included the use of Mobike bicycles as barricades, the burning of public property and vehicles, and looting – levels of violence that were undeterred by the standard anti-riot strategy of the Carabineros, water cannons and tear gas.

Then, on Sunday night, November 18, “cacerolazos” erupted across Santiago in a cacophonous demand that the Governor of the Araucanía region, Luis Mayol, and Interior and Public Security Minister, Andrés Chadwick resign.

On Monday night, November 19, a group of hooded protesters burned a public transit bus with a Molotov cocktail.

On Tuesday, November 20, a group set another public transit bus on fire near popular Bustamante Park. According to initial reports, the passengers and driver had to leave the bus quickly amid threats from the anonymous protesters.

The most recent series of demonstrations and violent acts occurred on Wednesday, November 21, after a candle convocation in memory of Catrillanca. It was then that a concentration in Plaza Baquedano cut off traffic and was involved in other minor incidents.

Mixed signals from the Government

Although rage has been accumulating for years within the radical groups that support the Mapuche demands, what primarily triggered their strong responses this time was the confused and confusing reaction of the Piñera administration after the death of Catrillanca.

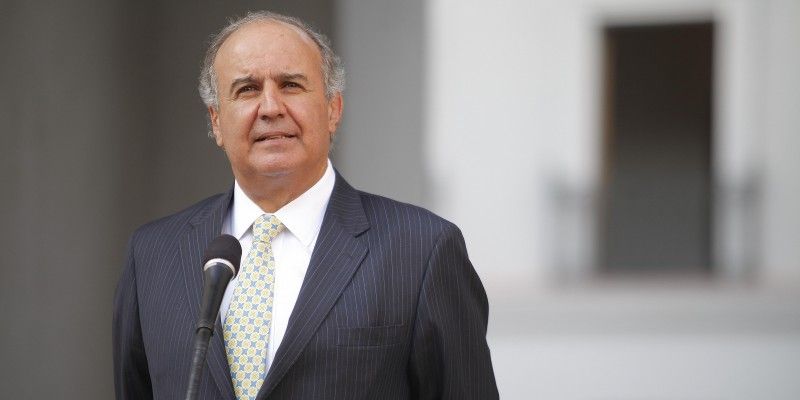

First, the administration announced that it would exhaust all means to “investigate the truth of what happened,” while, at the same time, publicly supporting the role of the Carabineros of “pursuing crimes.” Chadwick then reinforced the distrust between the different political and social sectors when he said that Catrillanca’s death “has nothing to do with the conflict situations that have occurred in rural areas derived from the so-called Mapuche conflict.”

After an initial denial by the police institution, the Government later confirmed that the Carabineros who participated in the operation that lead to Cantrillanca’s death were carrying surveillance cameras. Videos of that day, however, were later erased by one the policeman.

Because of that, Chadwick dismissed four Carabineros from the GOPE team who initially arrived at the scene. In addition, the Government accepted the resignation of General Mauro Victoriano, head of Order and Security of La Araucanía, and Iván Contreras, Prefect of the Araucanía forces.

Broken trust

The current administration now finds itself under a confidence cloud. This cloud has a name: “Operation Hurricane,” in which Carabineros special forces manipulated evidence against Mapuches comuneros during Bachelet’s second term.

Mistrust is not only in the minds of the Mapuches and the citizens. It is also evident in parliamentarians from the opposition parties, like Christian Democrat Senator and former Intendant of La Araucanía, Francisco Huenchumilla. He pointed to the political responsibility of the current administration and cast doubt on the version of facts offered by the Carabineros.

Days later, his party announced that they were launching a constitutional accusation against Mayol, a charge that triggered Mayol’s resignation on Tuesday. In his final press conference as Intendent he claimed, “I leave the position with the conviction that the La Araucanía region is much better than in March, when I assumed this challenge.”

The explanation offered for the erasure of the videos has only deepened the distrust, and some members of Congress were not convinced by the explanation General Director of the Carabineros, Hermes Soto, gave to the Chamber of Deputies.

During his public appearance in the Citizen Security Commission, Soto reported that one of the officials involved in the incident acknowledged that he destroyed the memory card, but only in order to eliminate intimate images with his partner, which he had recorded with the same camera.

Years of radicalization

Currently, the Piñera administration, like its predecessors, has been facing the conflict in La Araucanía with opposing methods: on the one hand, its Minister of Social Development, Alfredo Moreno, promotes a dialogue between the Mapuches and the owners of the lands. On the other, the Government installs the GOPE or “Jungle Command,” a specialized unit that has received training in Colombia and the United States to control violence.

And this last hardline approach, the administration says is justified because of a “situation of extreme violence” in the region that has resulted, according to the government, in 20 fires, 924 confrontations with firearms, 509 attacks on police institutions, and 542 roadblocks and obstacles.

Most of these episodes of violence (35%) are in Ercilla, a commune in the Region with a large population of Mapuches and a history of violent incidents. Ercilla is the same commune where Camilo Catrillanca was shot.These numbers and measures mark a new level of violence and radicalization from the Mapuche activists and the State.

This approach in law enforcement originated during the Ricardo Lagos administration. During his first three years in office the government deployed a strategy that combined, first, a political opening, recognizing the Mapuche people’s historical grievances against the Chilean State and providing social assistance with a certain culturalist approach; and, second, a plan of police “intelligence” with the unprecedented application of the Anti-Terrorism Law, a law that was aimed at promoting the isolation and criminalization of the most radical sectors of the movement, labeled judicially as “terrorists,” in full harmony with the post-11-S security framework.

After that, the protests were being led, not by the traditional Mapuche leadership, like the “lonkos” with their traditional attire, but by militant youngsters with Balaclavas, the most infamous of these new groups being the Coordinadora Arauco-Malleco (CAM).

The Piñera administration, lacking the clientelist networks and the social penetration that the old “Concertación” Coalition (center-left) had in the Mapuche people, responded to the new levels of violence from these groups with the deployment of a high-impact media strategy.

Shortly after the polemic trial against the “machi” Celestino Córdoba, condemned for assassination in the Luchsinger-Mackay case, the second Bachelet administration tried to start a new approach, this time promising the creation of a Ministry of Indigenous Affairs, the end of the application of the Anti-Terrorism Law, discussion regarding a new model of pluricultural coexistence and alternatives to the purchase of land for territorial restitution. None of these promises were completely fulfilled by her administration, although the Ministry of Indigenous Affairs should be launched next year.

The need for a democratic opening

The current scenario of the Mapuche conflict is critical, and an escalation of violence is highly probable in the short or medium term. As Roberto González, main researcher at the Center for Conflict Studies and Social Cohesion, asserted in an interview last year, the last 25 years have shown clearly that it is not repression, fear and violent protest that will resolve the conflict. The only answer that governments have yet to take is the democratic opening of political channels for the Mapuche people.

Until now, however, there has not been a real incentive for the abandonment of the most radical repertoires of contention.

In addition, such a change might not be accepted by the most radical groups, which have come to the conviction that radical action is the only way to regain total control of ancestral lands, a conviction that is rooted in the great deterioration of confidence in the Chilean state that the Mapuches have experienced and in historical debts they feel they are owed.

As Gonzáles also reminds us, the traditional Mapuche social organization, different from western ones, lacks a single head with which to negotiate and reach agreements. In the traditional Mapuche society organization, each community’s lonko is a specific authority, with a vision and method for solving the community’s affairs.

The Government needs to understand these differences if it wants to avoid a further radicalization of the conflict – a conflict that, since 2001, has cost the lives of 20 people, 15 of them Mapuches. If it keeps following the same path, there is a real danger that the Mapuches and Chilean society will become irrevocably severed.

*Imagen de cabecera propiedad de Chile Today.