Por TOMÁS CROQUEVIELLE H.

Licenciado en Historia y Periodista

Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile

While some believe that a proposed labor reform will provide flexibility and greater welfare to workers, critics think that it opens the door to job insecurity. The debate opens questions about the nature of the world of work in Chile. Whatever the outcome of that debate, change is on the horizon.

Chile, like most of the world, is living a profound transformation: The fourth industrial revolution (Industry 4.0) is coming. At a time when the reality of work is transforming rapidly, automation, flexibilization and competition become fundamental factors.

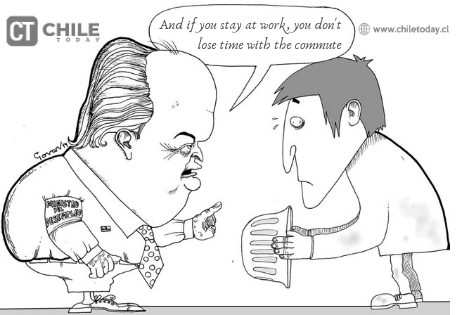

In that sense, the classic, if clichéd, paradigm of the worker who commutes to the office or factory from Monday to Friday in the mornings and works 8 or 9 hours is quickly becoming outdated.

Now, it’s supposedly all about greater adaptability, reconciliation of work and family, and the understanding ofemployment as a source of growth, education and training. And to accommodate the resulting novel forms of employment, these parameters require new legal standards.

To face this phenomenon, and after several days of consultation, the Piñera administration submitted a “Labor Modernization” proposal to Congress, in which it seeks to incorporate in the Labor Code an alternative, individually agreed, distribution of monthly working hours.

The draft bill includes the possibility of distributing 180 monthly work hours in different ways across the week. Employees could adjust them to a minimum of four days and a maximum of six but one workday may not exceed 12 hours.

Even economists like Andrea Repetto, José de Gregorio and Eduardo Engel, who are close to the previous center-left governments, have supported the reform and praised the possibility to distribute hours since “greater flexibility allows to improve productivity because it allows for options that today do not exist to organize the workday.”

Weak Unionization

However, opponents argue the law would neither improve working conditions nor allow for more family time since it would establish extremely long working days.

For critics, in a country like Chile, where only 20.6% of the private sector workforce is unionized, effective negotiations over working hours are stacked against each worker.

Hence, assuming everyone can individually strike bargains on working conditions and hours is as far from reality as thinking that a consumer can negotiate the service conditions with an internet or water provider.

Under the government’s plan, critics charge, fundamental rights such as the minimum wage, resting hours, overtime limits, or lunchtime duration will be at the discretion of the employer, opening the door to labor precariousness.

Adriana Muñoz of the left-wing Party for Democracy (PPD) and president of the Senate’s labor committee said that “we continue to sell the illusion that it is possible that workers achieve good conditions of adaptability or flexibility in an asymmetric [power]relationship” between the employer and the worker. Thus, Muñoz said, according to Emolnews portal, that the focus must be on unionizing since that would empower workers to negotiate through collective bargaining.

So, the debate will revolve around the views of those who believe Chile is ready to face the economy of the 21st century and those who think the current power structure at the workplace, still under the logic of the neoliberal precariousness, makes it impossible to advance flexibilization.

*Imagen de cabecera propiedad de La Nación.